Wi-Fi Signal Too Weak? We Put An Aluminum Foil Booster To The Test

Airports do it. Satellite dishes do it. Even giant radio telescopes do it. So why shouldn't you be able to focus your Wi-Fi signal in a way that makes it more useful? Some folks at Dartmouth think you should, and they've come up with a process for making Wi-Fi signal reflectors that will allow you to focus your signal where you want it. Best of all? This is basically an aluminum foil hack. The million-dollar question is if it actually works.

The challenge of reigning in Wi-Fi signals so that they can be directed efficiently is daunting. One big reason is that the signals are fragile, prone to being weakened by walls, can be cut off entirely by anything metal, and are severely diminished over distance. The old 2.4 GHz Wi-Fi band has trouble with other microwave devices, while the 5 GHz band is faster but has less range and tolerance for obstacles like walls. The interference problem can be severe for all Wi-Fi because the more complex the environment and the more convoluted with Wi-Fi devices, the more multipath interference rears its ugly head. Basically, there are signals flying every which way, often destroying the one you're paying attention to at the moment.

Most of this can be improved, at least theoretically, by placing a homemade reflector behind your Wi-Fi antennas and shaping it in such a way that your signal gets bounced to all the right places. The questions that remain are: Is this something you can do at home, are there better ways to manage it, and are you better off learning how to connect an outdoor Wi-Fi antenna to a router?

Setting up an oversimplified test of an over-complicated problem

My idea was to build a reflector, following the researchers' process as closely as possible, and see if it made a measurable difference in how easily I could direct my Wi-Fi signal. In spite of having more I.T. infrastructure than some corporate headquarters, my house has the worst Wi-Fi router I have ever owned, thanks to my recent switch to fiber. This means I didn't have to worry about my router corrupting my results by improving what I was trying to otherwise improve.

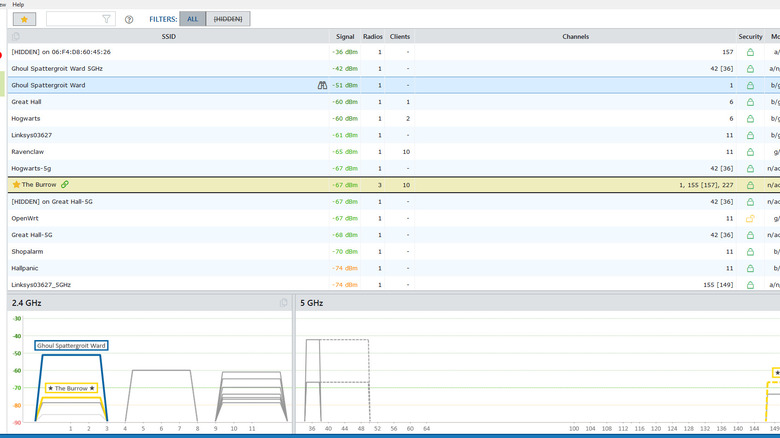

I tested the hack on one of three active access points in my house as well as on two desktop PCs, a laptop, and an iOS phone. For the desktops and laptops, I used three network monitoring applications: WiFi Analyzer, inSSIDer, and NetSpot. On the iOS phone, I used WiFi Analyser and the mobile version of NetSpot. The idea is to identify at least three points (I settled on four) from which Wi-Fi signals can be measured before and after my reflector was installed. I ended up with one point opposite the reflector, two in the focus zone in front of the reflector, and one in a zone to the side that should show a diminished signal strength.

To say that all of this ended up being extremely unscientific is an understatement, and it got worse as it went along. If nothing else, as you can see from the screenshot, I identified a lot of potential interference that's zooming around in my house. And, at a minimum, I should be able to figure out if the reflector notion works in principle.

Coming close to the experiment, without really coming close

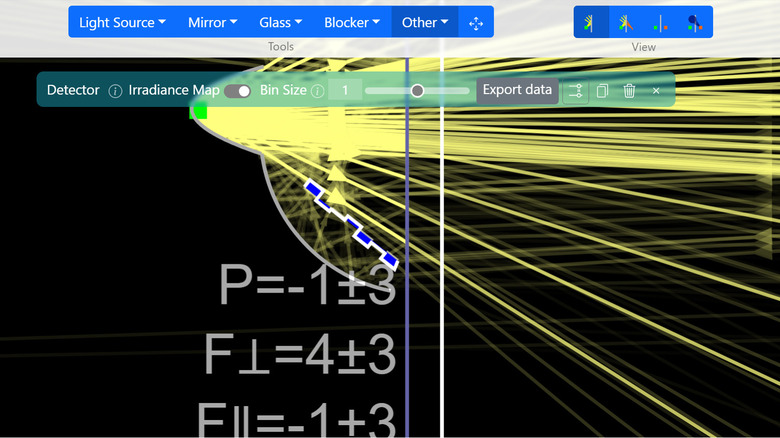

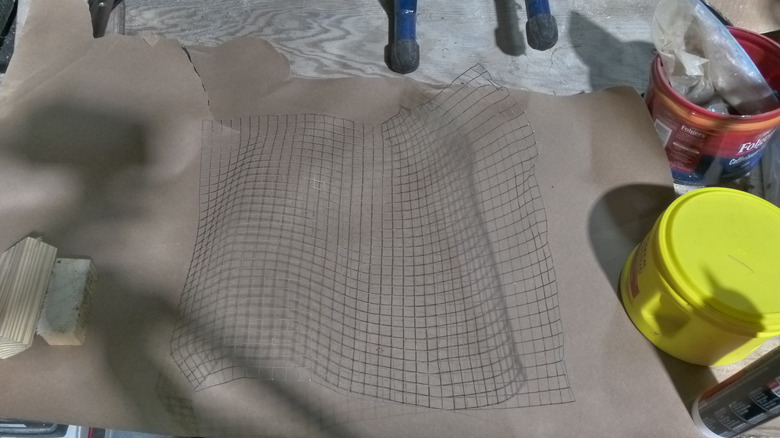

The main problem with Dartmouth's big reveal is that they don't make their tools available to the general public. What their software did was basically to model a space, Wi-Fi radio waves, and a customizable reflector to see where the signal might be mechanically directed. The tool I used for attempting to model reflectance and transmission through walls and the like, Ray-Optics, was a bit coarse for the purpose and only worked in two dimensions (parallel to the floor). At some point it became obvious that I wasn't going to produce better results 3D printing a model from Ray-Optics than simply forming one by hand using the general information gleaned via the light modeling. (I'll readily acknowledge that I was quick to accept this conclusion because my 3-D printer was doing overtime printing costume accessories for Dragon Con, which my two oldest kids attended as the Witch King of Angmar and Studio Ghibli's Arrietty. It was like having cognitive dissonance itself personified and demanding fast food from the backseat.) So, I constructed my reflector by hand from ¼-inch hardware cloth covered in aluminum foil, with a block of wood attached to its front and back sides to act as a stand.

One other snag: I ended up jettisoning the NetSpot mobile data gleaned from my phone because it doesn't report the Wi-Fi signals' strength in dBm, but instead relies on standard speed tests like you use when Prime Video keeps doing the spinny buffering thing. So, I standardized on dBm and tossed the NetSpot data.

What about beamforming? Said no one ever

Let's take a moment to talk about beamforming. As I read through the Dartmouth paper, I kept thinking, "Why not just use beamforming to do the same stuff?" Beamforming is a technology that has been around since Wi-Fi 4 and has matured with Wi-Fi 6 and 7. It uses multiple transmitting antennas to concentrate a signal in a particular direction, using constructive and destructive interference to direct and "focus" a Wi-Fi signal. That is, it strengthens the signals going in the right direction and messes with the ones going elsewhere, which is not unlike what the Dartmouth research promises. That paper's authors seem a little defensive about beamforming technology, and make what feels like superficial claims about the superior security of the reflectors and the high cost of beamforming. But beamforming is integral to Wi-Fi 7 and can also be found on older devices, like sub-$100 models from big names like Netgear and TP-Link, and doesn't seem exorbitantly expensive or dangerously insecure.

From that point of view, beamforming could do a lot of what Dartmouth is trying to do. And, perhaps more importantly, beamforming might work against Dartmouth's reflector notion. Consider the problem of wavelength and phase cancellation – the nullification of a signal that's reflected at the right distance from its source point. There's no way to know the optimal distance at which to place a reflector to minimize destructive interference that could undermine beamforming. The Dartmouth effort feels beset with a chaotic array of factors that might call for a technological solution (like beamforming) rather than a physical solution.

Interfering with bad Wi-Fi seems to make it worse

To be blunt, it did not go well. I identified 11 data points that should improve with reflector use, seven that should experience a decrease in signal quality, and 13 that fell outside of the reflector's direct influence but which might show the effects of increased interference. Of the 11 that should have improved, only three did. On the other hand, six of the seven that should have declined did. If this data were reliable, you might conclude that this technology is somehow best at disimproving certain signals, but not great at improving them. Worse still, I left the reflector in place for a couple of weeks, and the machine to which I was trying to direct a stronger signal performed so poorly, and so unusually, that I ended up removing the reflector in a fit of pique.

But since neither my data nor my subjective observation is altogether reliable, there's a more moderate conclusion you might reach: This undertaking is far too complicated for my methodology, and possibly too complicated for the Dartmouth team's. Their approach to minimizing interference was to "leave it for future work," but minimizing interference is most of the work to be done, and (unlike their experiments) real-world scenarios will involve reflective surfaces, obstacles that are partially transparent to Wi-Fi signals, multiple access points competing for signal clarity, and maybe even chicken wire contributing to terrible Wi-Fi. The goal — successfully modeling all of this activity and outputting what looks like a severely damaged satellite dish that will precisely focus a Wi-Fi signal — sounds, let's say, optimistic.