Subway Tile's Fascinating Evolution From Below To Above Ground

It was 1901, and architects George C. Heins and Christopher Grant LaFarge were working on what would become one of the largest and most influential commissions of their lives: the first New York City subway stations for the Interborough Rapid Transit Company. The duo, known for their designs at the massive Cathedral of Saint John the Divine and the Astor Court buildings at the Bronx Zoo, were in search of the right cladding to cover the interiors of what was primarily a huge, subterranean infrastructure project made out of steel trusses, brick walls, and terra cotta ceilings.

When was subway tile invented?

When was subway tile invented?

They needed something that would effectively soften the strongly industrial feel of the dark, cave-like spaces of the waiting platforms, tunnels, and ticket booths, and so the material had to be durable, bright, and, perhaps most importantly, easy to clean — a top priority in a society that equated cleanliness with respectability. Ultimately, the architects settled on what would become an iconic material not just in public transportation but also in the kitchens and bathrooms of millions of private homes: the so-called "subway tile."

What are the benefits of subway tile?

What are the benefits of subway tile?

Measuring 3 inches by 6 inches (a satisfying 1:2 ratio) and with a shiny, non-porous glazed coating, these tiles were ideal because their smooth surface could be cleaned with a quick wash or wipe with a damp cloth, and their production by industrial methods ensured that they were widely available and easy to install. Heins and LaFarge selected a brilliant white color to brighten up the passenger spaces, and the highly reflective finish bounced light from both the yellow-tinted incandescent light fixtures and any daylight that made it down into the underground areas through multiple skylights.

The tile, originally called "white ware" because it was only available in white (and easier to see dirt and dust on), and was laid up in what was called a running bond pattern (where the seams alternated across each row), felt like a familiar version of brick patterns.

When the first line of subway stations opened to the public in 1904, their above-ground control houses with token booths, turnstiles, gates, staircases, and subway platforms were praised as "excellent in the architectural propriety of their schemes of decoration." The Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide, a local real estate publication, noted that "something clean, neat and attractive was wanted; and the white tiles with colored borders serve the purpose admirably." The idea of using a simple ceramic tile with a dirt-deflecting glaze became the de facto cladding for other subway stations around the world.

When did subway tiles become popular outside subway stations?

When did subway tiles become popular outside subway stations?

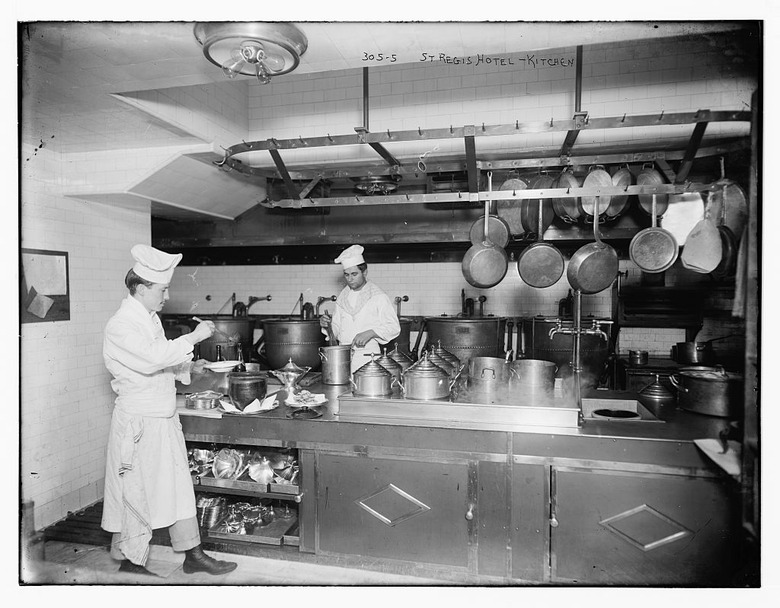

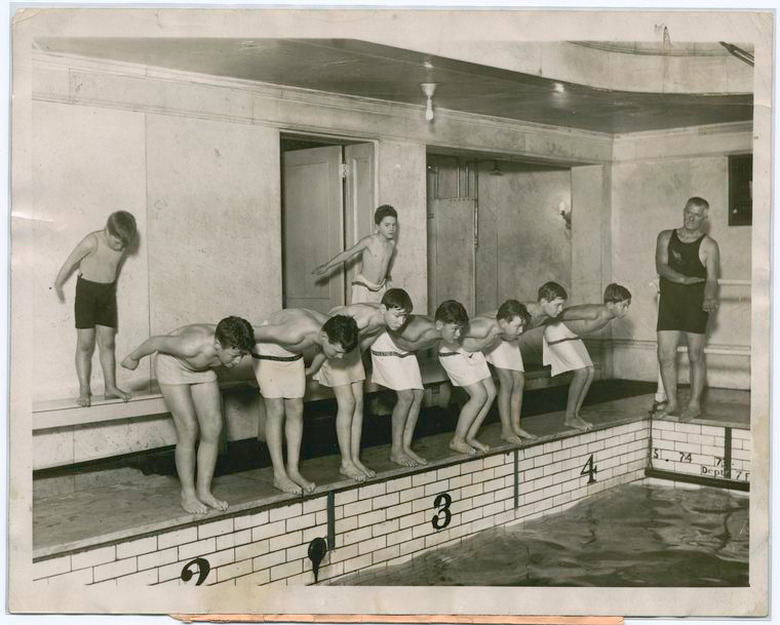

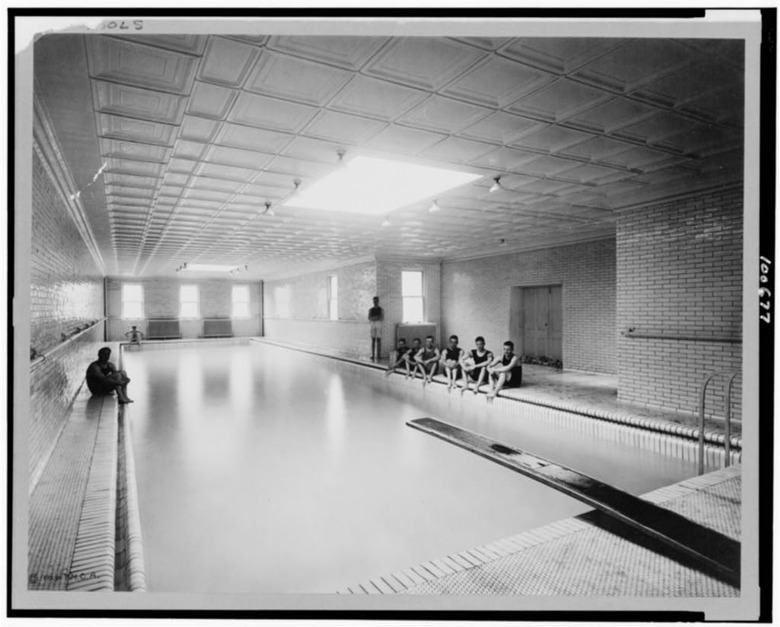

By the 1910s, the tile was considered such a hygienic, easy-to-clean material — and produced in such large quantities in industrial potteries and ceramics manufacturers — that it was introduced into hospitals, schools, religious buildings, shops, markets, and other public spaces. One manufacturer, Minton Tiles, suggested in a 1904 catalogue that "wall tiles be fixed from floor to ceiling" and noted that their white glazed tiles were recommended for "places where a reflection of light, or a pure and clean effect, is desired."

When did colored subway tiles become popular?

When did colored subway tiles become popular?

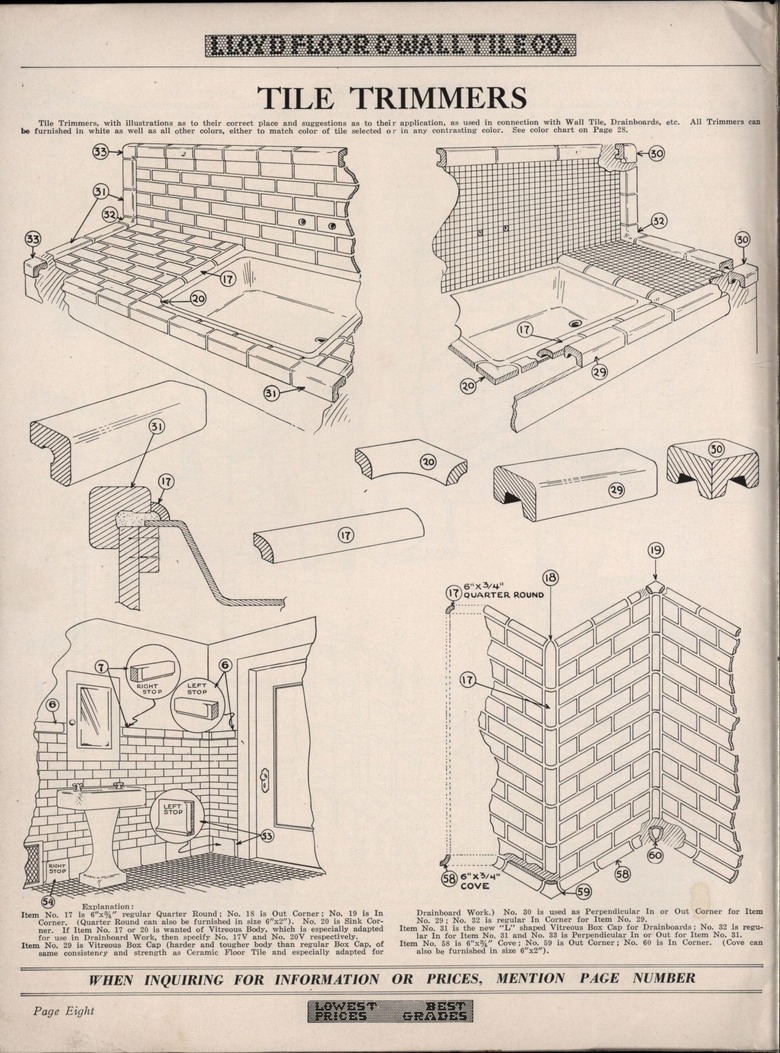

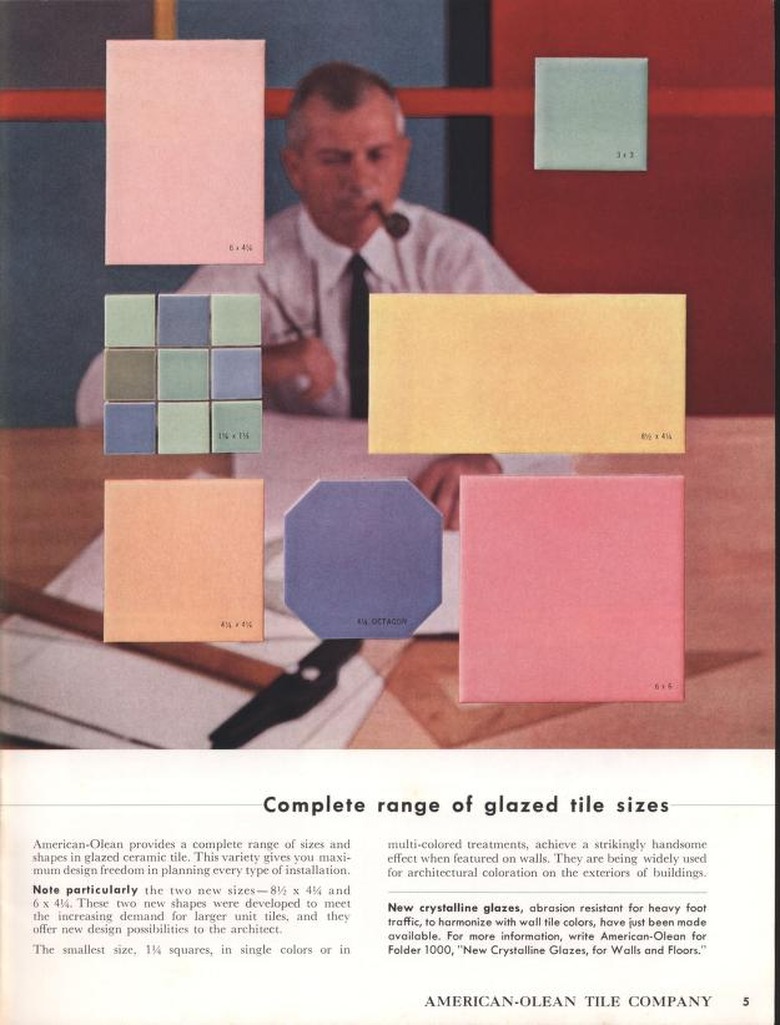

The material was so effective that it was also quickly used in homes, where it lined the backsplashes and walls of kitchens, bathrooms, and even hallways and basements where light and cleanliness were issues. However, it wasn't until the 1920s, with the influence of the Arts & Crafts movement, that most producers expanded their color palettes beyond white to glossy black, and later pastel tones like pink, light green, and pale blue. Manufacturers also started creating specialty pieces like curved corners, bases, and moldings that ensured that every inch and every tight corner could be reached and cleaned, but without sacrificing on style and detailed design.

By the 1930s, the popularity of the ever-versatile subway tile had peaked. An even broader selection of colors and textures was available, often paired with patterned tiles along borders and accent tiles in different colors and sizes, and manufacturers recommended tile be used as a sanitary surface everywhere from walls and floors to kitchen counters and window sills. Bathroom fixtures also started to come in a wider variety of colors, and often matched the subway tile on the walls in deeper tones like mauves, burgundies, and jade greens.

When did subway tile decline in popularity?

When did subway tile decline in popularity?

But by the 1970s and 1980s, subway tile had fallen out of favor. Other materials, like laminate backsplashes, acrylic faux-marble finishes, and linoleum tiles, felt more modern and exciting, and the fear of germs and the turn-of-the-century obsession with cleanliness and sanitation seemed old fashioned. Tiled murals with scenes of the Italian countryside graced the backsplashes of kitchens, bathrooms with carpet-covered toilet seats became all the rage, and simple subway tile seemed outdated and even too modest.

When did subway tile make a comeback?

When did subway tile make a comeback?

And while white and off-white tile reemerged in the 1990s as a popular choice in kitchens and bathrooms, it wasn't until the 2000s that the old-school subway tile would return as a simple, timeless finish — but this time with an even broader range of colors, sizes, and even materials. Patterns in bas-relief, subtle or bold textures, glistening metallic glazes, colored grout, and translucent glass tile have given the material a new life, and an interest in historic finishes that have stood the test of time only furthered the subway tile's resurgence.

But after well over 100 years, what has remained the same? In the end, it's the subway tile's combination of pleasing proportions — the small format, rectangular shape, and standard 1:2 or 1:4 ratio — and its versatility and easy maintenance, that have made it the enduring material that never fell too far out of fashion.